The beauty of imperfection

Throughout Western history, the concept of beauty has always been associated with the idea of perfection. In ancient Greece, the definition of beautiful was structurally linked to notions of order, symmetry and clarity, and to the presence of proportions defined as harmonic. In the Middle Ages, Christianity gave beauty a symbolic dimension by interpreting it as divine attributes, such as goodness and truth – in this sense, also linked to the idea of perfection. And although Renaissance brought relativistic concepts, which incorporated cultural and socio-economic aspects to the concept of beauty, it was not until the seventeenth century that subjectivity began to permeate the notion of beauty (thus giving rise to the concept of “taste”).

In the second half of the eighteenth century, the social upheavals in Europe created a favorable environment for the revival of Ancient Greece and Rome’s ideals of beauty, widely used in the representative images of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire. And it was precisely at that moment that Kant emerged, the first thinker to move the center of existence of beauty from the object to the subject. The division that Kant established between ‘judgment of knowledge’ (which creates concepts based on the object’s properties) and ‘aesthetic judgment’ (arising from the personal reaction of the beholder before the object) defined the foundations of contemporary aesthetics. The beauty is no longer only in what is seen, and also lies in the eyes that see.

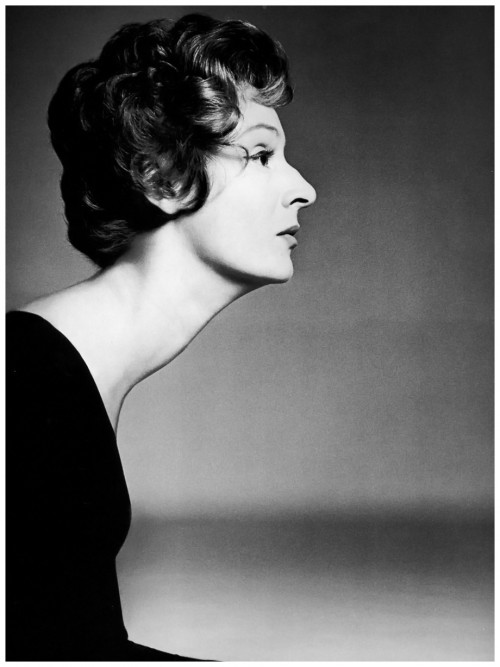

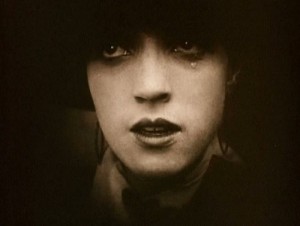

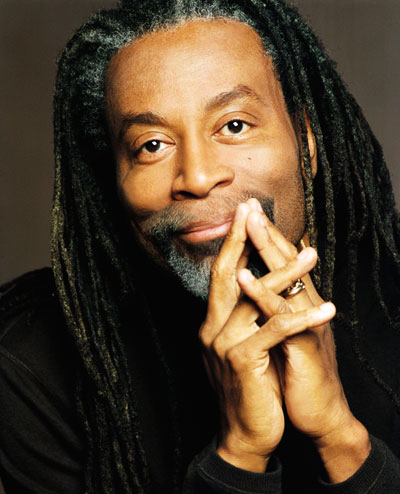

The Kantian thought paved the way for the great aesthetic ruptures that took place between the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. The ideas of uniqueness, individuality, pleasure, emotion, power, courage, vitality, and others, were incorporated into the concept of beautiful. We were able to understand that there is beauty in perfection, but also that perfection is not a prerequisite of beauty. We sharpened our capacity of perception and expanded the possibility of giving pleasure to our souls. We began to admire the crystal clear voice of Nat King Cole as much as Chet Baker’s insecure voice; the classic proportions of Grace Kelly’s face, and the exotic and voluptuous features of Sophia Loren; the dense beauty of Raushenberg’s work and the almost superficial pop art of Warhol.

A few decades later, the path of apparent freedom curiously ended up leading us to an imprisonment. Stimulated by an industry that is interdisciplinarily structured in mass production and overestimation of youth to generate profits, the search for a beauty ideal – for the perfect beauty – has never been as exacerbated as today. In an insane and endless process, men and women throw themselves on a journey towards that which is nothing but a collective imaginary construction. And by abandoning their own beauty to (try to) attain the other, they live eternally unhappy, wandering along this path.

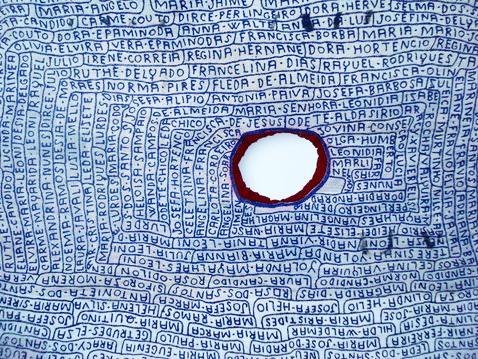

We need to rescue the wealth of plurality and the beauty that lies in imperfection. We need to remember the weirdness of Dovima. The eyes of Serge Gainsbourg, the teeth of Lauren Hutton. The mouth of Mick Jagger, the eyebrows of Frida Kahlo and the lines of Grace Jones. And, above all, remember the words of Leonard Cohen, who, in his song ‘Anthem’ from 1992, said:

“…Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.”